|

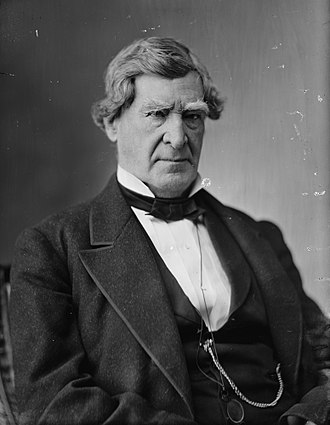

Department of State,

January 16, 1861.

Lieutenant-General Winfield Scott:

Dear General: The habitual

frankness of your character, the deep interest you take in everything that

concerns the public defense, your expressed desire that I should hear and

understand your views—these reasons, together with an earnest wish to know my own

duty and to do it, induce me to beg you for a little light, which perhaps you

alone can shed, upon the present state of our affairs.

1. Is it the duty of the

Government to re-enforce Major Anderson?

2. If yes, how soon is it

necessary that those re-enforcements should be there?

3. What obstacles exist to

prevent the sending of such re-enforcements at any time when it may be

necessary to do so?

I trust you will not regard it as

presumption in me if I give you the crude notions which I myself have already

formed out of very imperfect materials.

A statement of my errors, if

errors they be, will enable you to correct them the more easily.

It seems now to be settled that

Major Anderson and his command at Fort Sumter are not to be withdrawn. The

United States Government is not to surrender its last hold upon its own

property in South Carolina. Major Anderson has a position so nearly impregnable

that an attack upon him at present is wholly improbable, and he is supplied

with provisions which will last him very well for two months. In the meantime

Fort Sumter is invested on every side by the avowedly hostile forces of South

Carolina. It is in a state of siege. They have already prevented communication

between its commander and his own Government, both by sea and land. There is no

doubt that they intend to continue this state of things, as far as it is in

their power to do so. In the course of a few weeks from this time it will

become very difficult for him to hold out. The constant labor and anxiety of

his men will exhaust their physical power, and this exhaustion, of course, will

proceed very much more rapidly as soon as they begin to get short of provision.

If the troops remain in Fort Sumter without any change in

their condition, and the hostile attitude of South Carolina remains as it is

now, the question of Major Anderson’s surrender is one of time only. If he is

not to be relieved, is it not entirely clear that he should be ordered to

surrender at once? It having been determined that the latter order shall not be

given, it follows that relief must be sent him at some time before it is too

late to save him.

This brings me to the second question: When should the

re-enforcements and provisions be sent? Can we justify our-selves in delaying

the performance of that duty?

The authorities of South Carolina

are improving every moment, and increasing their ability to prevent re-enforcement

every hour, while every day that rises sees us with a power diminished to send

in the requisite relief. I think it certain that Major Anderson could be put in

possession of all the defensive powers he needs with very little risk to this

Government, if the efforts were made immediately; but it is impossible to

predict how much blood or money it may cost if it be postponed for two or three

months.

The fact that other persons are

to have charge of the Government before the worst comes to the worst has no

influence upon my mind, and, I take it for granted, will not be" regarded

as a just element in making up your opinion. " The anxiety which an

American citizen must feel about any future event which may affect the

existence of the country, is not less if he expects it to occur on the 5th of

March than it would be if he knew it was going to happen on the 3d.

I am persuaded that the

difficulty of relieving Major Anderson has been very much magnified to the

minds of some persons. From you I shall be able to ascertain whether I am

mistaken or they. I am thoroughly satisfied that the battery on Morris Island

can give no serious trouble. A vessel going in where the Star of the West went

will not be within the reach of the battery's guns longer than from six to ten

minutes. The number of shots that could be fired upon her in that time maybe

easily calculated, and I think the chances of her being seriously injured can

be demonstrated, by simple arithmetic, to be very small. A very unlucky shot

might cripple her, to be sure, and therefore the risk is something. But then it

is a maxim, not less in war than in peace, that where nothing is ventured

nothing can be gained. The removal of the buoys has undoubtedly made the

navigation of the channel more difficult. But there are pilots outside of

Charleston, and many of the officers of the Navy, who could steer a ship into the

harbor by the natural landmarks with perfect safety. This, be it remembered, is

not now a subject of speculation; the actual experiment has been tried. The

Star of the West did pass the battery, and did overcome the difficulties of the

navigation, meeting with no serious trouble from either cause. They have tried

it; we can say probatum est; and there is an end to the controversy.

I am convinced that a pirate, or

a slaver, or a smuggler, who could be assured of making five hundred dollars by

going into the harbor in the face of all the dangers which now threaten a

vessel bearing the American flag, would laugh them to scorn, and to one of our

naval officers who has the average of daring, ' the danger's self were lure

alone! '

There really seems to me nothing

in the way that ought to stop us except the guns of Fort Moultrie. If they are

suffered to open a fire upon a vessel bearing re-enforcements to Fort Sumter,

they might stop any other vessel as they stopped the Star of the West. But is

it necessary that this intolerable outrage should be submitted to? Would it not

be an act of pure self-defense on the part of Major Anderson to silence Fort

Moultrie, if it be necessary to do so, for the purpose of insuring the safety

of a vessel whose arrivalat Fort Sumter is necessary for his protection, and

could he not do it effectually ? Would the South Carolinians dare to fire upon

any vessel which Major Anderson would tell them beforehand must be permitted to

pass, on pain of his guns being opened upon her assailants ? But suppose it

impossible for an unarmed vessel to pass the battery, what is the difficulty of

sending the Brooklyn or the Macedonian in ? I have never heard it alleged that

the latter could not cross the bar, and I think if the fact had been so it

would have been mentioned in my hearing before this time. It will turn out upon

investigation, after all that has been said and sung about the Brooklyn, that

there is water enough there for her. She draws ordinarily only sixteen and

one-half feet, and her draught can be reduced eighteen inches by putting her

upon an even keel. The shallowest place will give her eighteen feet of water at

high tide. In point of fact, she has crossed that bar more than once. But apart

even from these resources, the Government has at its command three or four

smaller steamers of light draught and great speed, which could be armed and at

sea in a few days, and would not be in the least troubled by any opposition

that could be made to their entrance.

It is not, however, necessary to

go into the details, with which, I presume, you are fully acquainted. I admit

that the state of things may be somewhat worse now than they were a week ago,

and are probably getting worse every day; but is not that the strongest reason

that can be given for taking time by the forelock?

I feel confident that you will

excuse me for making this communication. I have some responsibilities of my own

to meet, and I can discharge them only when I understand the subject to which

they relate. Your opinion, of course, will be conclusive upon me, for on such a

matter I cannot do otherwise than defer to your better judgment. If you think

it most consistent with your duty to be silent, I shall have no right to

complain.

If you would rather answer orally

than make a written reply, I will, meet you either at your own quarters or here

in the State Department, as may best suit your convenience.

I am, most respectfully, yours, &c,

J. S. Black.

|